Randall's Story

"Visitors to our shop always ask how I got started. I’ve been asked so many times, the guys told me to write it down. So here it is:"

"Music is in my blood. And building vacuum tube amplifiers has become my personal art."

Randall Smith

President & Designer

My earliest memories are musical. I can still remember lying in my crib and hearing my dad play his tenor sax. He had a hotel dance band and a radio show for a couple of years after the War. He was also first chair clarinet in the Oakland Symphony so there was a lot of music in the house, live music. My sister was five years older than me and an outstanding piano student, so I clearly remember hearing her play Beethoven, Mozart and Chopin piano sonatas. Those timeless melodies and harmonies imprinted my infant brain and profoundly affected my mood.

So, my brain was processing music long before words began to make sense! Too bad rock ’n roll hadn’t been invented yet or I might have been a partying maniac bouncing in that crib to Roll Over Beethoven instead of Moonlight Sonata!

My first experiences with the mystical quality of musical instruments included the funky smell of my Dad’s open sax case and the magic that filled the house whenever he played. Many times, my mother said, “He wooed me with his tone” remarking on how they met and fell in love. When my father began teaching me clarinet —which he insisted came before sax or flute, he had me play one note for days until I had it pretty well mastered before he would show me the next one. I wanted to play ALL the notes in a burst of joy, like Benny Goodman –but Dad was really teaching how to Hear Tone, picking out all the separate elements, and how to Make Tone by bringing them together in a musical voice. Of course, that’s been essential knowledge for voicing an amplifier.

Around the time Leo Fender built his first guitars, a Canadian guy named Ernie, who worked for my father, introduced me to tubes. That was the era, way before stereo, when hi-fi was a new concept and something you had to build yourself. He had a studio quality turntable with a futuristic tone arm all mounted to a slab of exotic hardwood, and supported by four empty beer cans …Hamms, as I recall. Later, he gave me some of his older pieces, hand-built on the kitchen table, which I experimented with until I was 10 or 11.

The Original Home of Tone

The Doghouse Workshop in Lagunitas. Crescent moons on door are remnants from the original Princeton baffle boards, having been cut out to hold 12” speakers.

Then, at this impressionable age, I met Stan Stillson, a guy whose business was building industrial control systems in his garage shop. (His father had invented the Stillson wrench.) His son Dave, three years older than me, was into building hi-fi and ham radio gear as a hobby. I originally went to his father to earn a Boy Scout Woodcarving merit badge, which I thought would be easy. Was I ever wrong! The requirement for the badge seemed simple: Carve Three Items. Well, when I took my carvings over, I started worrying as soon as the guy opened the door. He was a Marine Combat veteran and scowled like Clint Eastwood on a bad day …tough as nails. I handed him my carvings and he gave me this withering look then said, “Follow me.” We crossed his shop floor. “This is a band saw,” he said, turning it on. “Here’s how it works.” He stacked my three carvings in a pile, glanced at me, then ran them through –first one way, then the other. He looked me in the eye as he tossed the pieces into the trash barrel. “That’s what I think of your projects. And that’s what I think of you.”

Busted! Totally Busted! See, his theory was that when a person makes something, they’re leaving behind a permanent artifact that reveals their values at that time. “Either you’re hopeless or you didn’t try very hard” he said, giving me the dead-eye cop stare. He knew I hadn’t put much effort into the carvings, and he was not about to offer any false praise to “build up my self-esteem”.

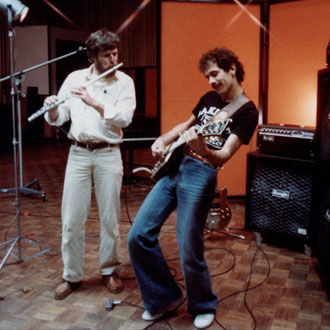

Randy & Carlos jammin’ in the 70’s

No, they were not good and I was called out for not caring enough . . . this became a very big and permanent life lesson. But, severely humbled, I hung around and tried to EARN that merit badge. I was in his shop for weeks, carving things, learning how to handle and sharpen his tools and how to work in a serious shop with a real craftsman.

With summer ending, I asked him if I had finally earned that badge. You know what he did? . . . . He pulled up a stool and told me to sit there for 20 minutes remembering how I was when I first arrived. After that, he would ask ME if I had earned that badge! Then, hesitating, I cautiously said YES - - and he agreed. Life’s best lessons are usually the toughest ones and that one surely shaped my character . . . and launched my life! Here’s why . . .

At that time, he was building a control console for the Nautilus, our first nuclear submarine. Right in his garage shop. That’s how heavy he was. And the things he built just floored me, they looked beautiful, cool, and so intrinsically right. They exuded artistry far beyond their primary, functional purpose and inspired me to want to do the same – to create “industrial art”. From then on, his son and I spent most our time in the old man’s shop, learning to hand-build amplifiers, transmitters, and modulators from scratch. All using vacuum tubes.

A few years later my interests turned to cars, girls, jazz and blues. By the mid-Sixties, I was playing drums in a band while going to university –the radical Cal Berkeley. One night on a gig, my friend Dave Kessner’s Sunn 200 amp went up in flames and smoke. Next day, I offered to fix it for him because we didn’t have two nickels between us. He looked worried but finally consented when I assured him I ‘would do no harm’. I bought resistors and capacitors from the electronics store and soon had that burned-up amp working like new again.

Kessner was a street-smart kid from LA and he was floored I could fix it. But I was more floored when he suggested we open a music store together. “What do we know about running a music store?” I asked, shocked at the idea. He said, “We’ll sell some of our band gear. I found a store front for $75 a month. I’ll run the front and you can fix stuff in the back.” …which turned out to be the meat locker of an old Chinese grocery store. Dave was right about the demand: so many bands in the SF Bay Area back then and no one to fix the gear! I felt a huge responsibility to do things right because in no time our customers at Prune Music (yeah, right) included the heavies of the SF scene: Big Brother, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, The Sons, Quicksilver, Santana, Steve Miller and so many more you’ve never heard of. Finally, sick of the riots in Berkeley, we moved across the Bay to charming Mill Valley at the north end of the Golden Gate.

Around 1969 we wanted to play a prank on Barry Melton of Country Joe and the Fish. So I took his little Fender Princeton practice amp which, stock, puts out about twelve watts into a ten-inch speaker. I cut up the chassis to fit big transformers and entirely rebuilt it using the famous 4x10 Tweed Bassman circuit. After careful measurement, I cut out the speaker board and squeaked in a twelve-inch JBL D-120, the hot speaker back then. When I finished building it, I took it out to the front of the store to get a good play test and who happened to be hanging out right then? Carlos Santana.

One of the original modified amps for Carlos Santana

He just wailed through that little amp until people were blocking the sidewalk. When he stopped playing he turned and said, “Shit man. That little thing really Boogies!” Word spread fast and before long there were over a hundred little Princeton/ Boogies appearing on Bay Area stages including the Fillmore and Winterland …all of them built up a dirt path in a mountain shack I had converted from an old dog kennel. (It became too hard to get work done at Prune as the shop area had become a notoriously hip “hang zone” with everyone from Clapton to Santana chilling out there, fragrant herb always wafting . . .

So…what’s MESA? The Bay Area was running out of Princetons to modify and I needed to augment my paltry income from the music store so I moonlighted two other gigs. One was jacking up old country houses in West Marin, digging footings and pouring concrete foundations underneath, starting with my own. That old summer house was nearly falling down but I was skinny enough to crawl into the tightest spaces and dig. They called me The Mole! (I always wanted my first name to be “The”.)

My other gig was rebuilding old Mercedes-Benz engines in a two-story garage/studio I had built with wood trucked down directly from the saw mills. (The truck was so overloaded we had to drive five miles through a pear orchard to avoid the Highway Patrol weight station!) I had grown up with a little Austin-Healey Sprite, which is very ‘character building’ in the sense that it broke often and forced ingenuity …just to make it home! It required an engine rebuild every couple of years so when I got an old ’59 Mercedes with a blown engine, I wasn’t afraid to give it a try. For $75.00 spent on parts and machining, that engine ran strong for another 100,000 miles! And that started an ‘old Mercedes’ trend among my friends. Those engines were an inspiration and the difference between them and the British motors was shocking. It was yet another lesson in the virtues of “getting it right”.

The Mighty MESA Bass 450

I needed an official sounding name to buy pistons from Mercedes, ready-mix trucks full of concrete and of course amp parts. “Mesa Engineering” (a name I made up on the spot) seemed familiar and professional sounding. One day my country bliss was interrupted by a tough but friendly stranger from the ‘hoods of Oakland who showed up on my back porch. He’d heard the Princeton/Boogies and wanted an amp. He was a bass player —but he still wanted me to build him an amp and I sorely needed the 300 green dollars he was literally stuffing in my shirt pocket. He wouldn’t take no for an answer.

So the first Mesa amp was a snakeskin bass amp made for ‘the inimitable’ Patrick “Buzz” Burke, a lovable thug who’s still a top lifelong pal. He became such a good friend, I later traded him my half ownership in Prune Music for a guitar! The fact that this total stranger was trusting me with the astonishing sum of $300. inspired me and I promised I would build him the best bass amp ever. Fifty years and countless gigs later, that one-and-only Mesa Bass 450, serial #002, still has tone. (There is no #001)

The first Mesa guitar amp I scratch built was a Boogie® 130 Lead Head, also snakeskin, which English rocker Dave Mason took on the spot when I showed up at a Winterland sound check. It paid homage to that classic 4x10 tweed Bassman circuit - - that is so great for guitar, but so lousy for bass!

Even with the success of those dozen or so snakeskin heads, I was still hearing a tone in my mind, more like a sax, with harmonic richness and long sustain. For years guitar players had been complaining about the limitations of their amplifiers – amps that now would be considered hot vintage prizes. The main complaint was that ‘loudness’ and ‘overdrive characteristics’ were inseparable. There was only the one volume control and thus no way to get the amps to break up expressively without being at max loudness. Some players were having Master volumes added to their amps. But I didn’t offer that mod because there wasn’t enough gain in the standard Fender circuit to do much. Everyone had that complaint, especially Santana. Even with his jacked up Princeton, he couldn’t always get enough sustain. Turns out we were both after the same elusive sound - - rich harmonics with endless sustain.

Original MESA/Boogie® Mark I

Then as a result of a pre-amp project I was building for Lee Michaels to drive his new monster Crown DC 300 power amps, I stumbled onto the Holy Grail. I didn’t know how much signal the Crowns needed to drive them so I thought I’d cover my basses by adding an extra complete stage of tube gain to the basic pre-amp architecture, adding three variable Gain controls at critical points in the circuit. When we hooked it up in Lee’s studio, it didn’t work at first because he mistakenly plugged the speakers directly into the pre-amp. We kept turning up the three gain controls because we could hear a faint little sound. Then, when we plugged it in right, Lee hit a big power chord and practically blew our bodies through the back wall! We looked at each other with big grins and got down to adjusting those Gain controls. It was monstrous! You could dial in previously un-heard of amounts of gain with the first two controls while adjusting the loudness level with the third control. It was huge sounding and it would sustain forever. That was the beginning of high-gain cascading pre-amp architecture. This wasn’t an incremental increase of 50 or even 100 percent, this was an increase of 50 TIMES the normal gain of an amplifier and an entirely new realm of performance.

I knew at the time this was a real breakthrough and I couldn’t wait to build up a Boogie size 100 watt combo for Santana using four 6L6s. I was pretty sure it would do just what he’d been searching for. And it came together just in time for his great Abraxas tour which introduced this new high-gain sound to the world and started putting that mountain studio on the map as the Home of Tone®.

At first, I was hand-building all parts of these early Boogies by myself including silk-screening the control panels and etching copper printed circuit boards in a hot acid bath. I formed and punched the sheet metal chassis and built and finished the cabinets all with skills I had learned back in the ex-Marine’s shop. As demand grew, I enlisted the help of my wife and some neighbors. Mike Bendinelli who, at the time was painting the ceiling, was put to work on power supply boards and over 40 years later remains the keeper of the archives (mostly in his head) and the best restorer of those early amps. Back then it was a true cottage industry with various friends doing sub-assemblies all right there in the mountains of West Marin.

Randall Smith and Mike Bendinelli

At one point I was returning from my daily exercise of walking up the mountain behind the house with the dogs and swimming (illegally!) in Kent Lake. As I came back down through the redwoods, I could see the girls sitting on the deck, stuffing circuit boards in the sun with their tops off. I just stood there for a couple of minutes realizing that I had achieved the gig-bliss (for me at least!) and I told myself never to stray too far from the contented, productive and creative feeling of those happy times.

By the time we moved Mesa out, that mountain “house” had grown into a 4,000 square foot mini-industrial zone with a wood shop, electronics shop, loading dock, two offices and several full time employees. Before we left there, we were exporting to 39 foreign countries. I want to stop right now and give thanks to everyone involved. And that certainly includes all the musicians who trusted us with their cash and their tone. Thank You All So Much! In total we built around 3,000 Mark I Boogies in that house.

Looking back, I guess we were the first "boutique" amp company, though I never thought of it that way. Now, 50 years and 30 miles from that original Tone Shack, we’re still hand-building Mark Series amplifiers and quite a few other models. We’re no longer the latest underground boutique darling but we’re still pioneering the frontiers of tone with over 20 patents. And we’ve barely changed the way we design and build our amplifiers. What changes we have made are all based on my decades of experience as the designer and builder. And every little thing is calculated for one purpose only: To Hand-Craft A Better All-Tube Guitar Amplifier.

Each chassis is still hand-wired, checked out, teched-out and as always, bashed repeatedly with a hammer while turned full up!

Each chassis is still hand-wired, checked out, teched-out and as always, bashed repeatedly with a hammer while turned full up. Then there is a play test, followed by a 24-hour burn-in, another electronic check, installation into a cabinet and a final play test given by a different musician then a last inspection before packing. Every Mesa/Boogie® from the most expensive to the least uses the identical top grade materials and assembly techniques. Every Mesa/Boogie including all the cabinets, is entirely made in our one location here in Petaluma, California where we’ve been since July 4, 1980.

These days many manufacturers choose to have their products built out-of-country, and that’s OK with us. We look to a couple of our favorite icons and take heart: a Ferrari wouldn’t be the same if it were made in China. And closer to home, Harleys deserve to be made in Milwaukee, not Mexico, because they – like us – are American. In fact my Grandmother came to California in a covered wagon and told me all about it. A true pioneer!

.jpg)

In 2020 MESA/Boogie merged with Gibson, the oldest, most respected builder in the Music Instrument industry.

In 2020 we merged with Gibson, the oldest, most respected builder in the Music Instrument industry. As I turned 75 years old then, this alliance provides longevity for our Crew and Company past my time. Meanwhile I’m still here, doing what I love every day – designing amps, laying out circuit boards, drawing up chassis and hanging with musicians. The leaders of Gibson understand and appreciate the gem that is Mesa/Boogie and want to preserve our soul and our operations just as they’ve always been, and they’re great guys or we wouldn’t have partnered with them.

I promise we won’t let our increased visibility spoil us. This is what we do, and we love doing it. Our goals remain unchanged from Day One: Build the best musical amplifiers possible, with no excuses; and treat each person as we would wish to be treated, with no exceptions. We want every musician we serve to become a happy member of the Mesa/Boogie Family. Personally, I give huge Thanks to everyone for helping me evolve into what I must have been born to do. And that legion of fans world-wide is both a reward and a constant reminder: Stick to those Founding Principles and Don’t Mess Up the Magic!

Thanks & Cheers!

Randall Smith

Designer & Founder